The Biomimicry Strategy: An Executive Overview

Nature as Mentor: Why We Look to 3.8 Billion Years of Evolution for Inspiration.

3.8 Billion Years of R&D Mimétique (Biomimicry): Innovating with Nature’s Wisdom

Mimétique, also known as Biomimicry, is a strategic, interdisciplinary practice. This revolutionary approach positions life on earth as the ultimate research and development department.

Biomimicry goes beyond simple aesthetic imitation. Instead, it explores profound engineering solutions, these strategies honed over 3.8 billion years of evolutionary pressure!

Naturemimétique seeks to translate nature’s genius into scalable, ethical, and profitable human innovations, by studying these time-tested strategies.

We identified three foundational questions:

The Design Translation

This question focuses on the practical application of biological wisdom, asking things like, how can we imagine applying this natural strategy to human design?

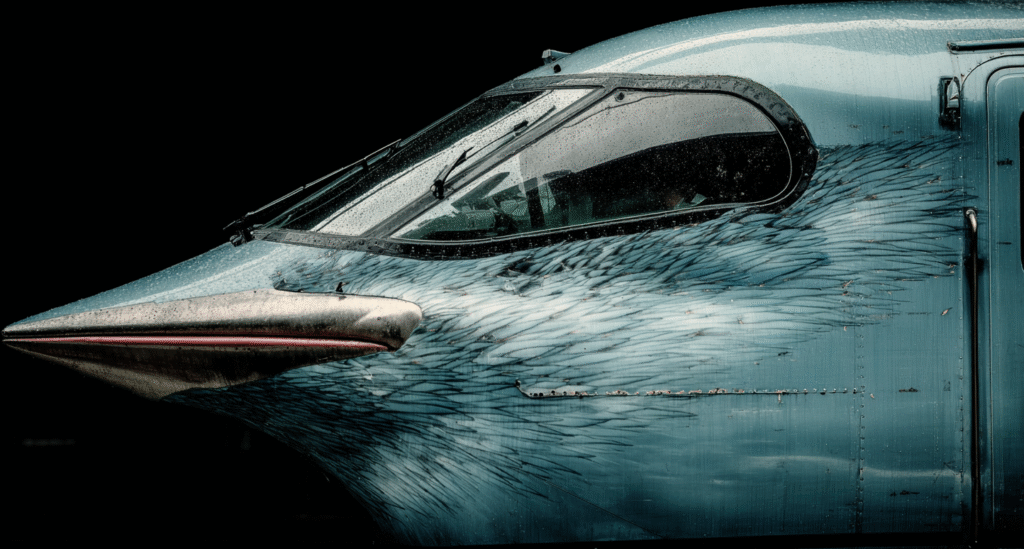

We focus on abstracting the core principles. For example, we explore theoretical applications, such as deriving high-speed train designs from the Kingfisher’s beak. This translation involves taking the core biological solution and applying it to a human-made context.

The goal can be broad: to develop new materials, design efficient systems, create sustainable processes, and to even rethink entire industries based on nature’s already proven designs and intelligence. Innovations must be effective and economical, but they also must be inherently sustainable and harmonious with the planet.

Life’s Challenge

This initial question touches on the fundamental problems that nature seems to have already solved.

We focus on natural phenomena as inspirational case studies. These examples include themes like self-cleaning lotus leaves and the structural lightness found in bones.

Many successful solutions exist: Consider the ability of lotus leaves to remain pristine (by self cleaning). Another success is the remarkable strength-to-weight ratios found in bird bones and plant structures (structural lightness).

Finally, we examine the processes by which organisms create complex materials without toxic byproducts. By understanding the solutions found in nature, we gain insights into sustainable and efficient design.

The Biological Strategy

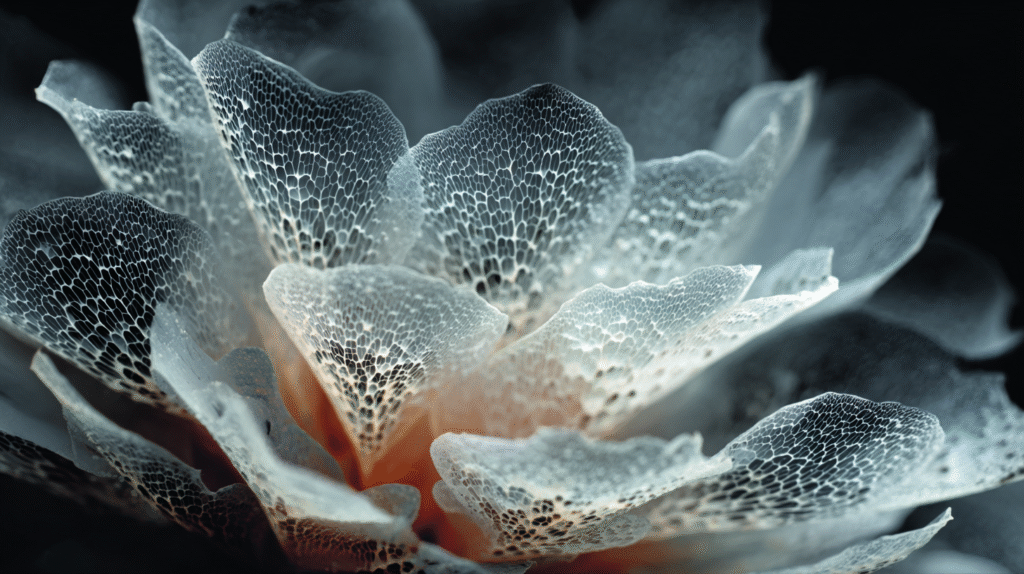

We discuss the functional mechanisms discovered in nature. This might mean understanding the microscopic structure behind a lotus leaf’s superhydrophobic properties.

Alternatively, it could involve dissecting the cellular organization of a bone to uncover how it achieves both lightness and strength. This stage emphasizes the crucial link between function and form in nature.

Naturemimétique is a powerful framework for sustainable innovation. It offers a systematic approach to inspiring solutions that are resilient, resource-efficient and even life-friendly. It encourages us to stop seeing nature just as something to protect, and start seeing it as an indispensable teacher on the road to a more sustainable future.

1. Form, Structure, and Aesthetics (The Design Challenge)

At this level, we explore the fundamental principles of physical geometry and efficiency that we see at work in the natural world.

We study how the shape, texture and surface organization of living things contribute to their performance and resilience. And what’s even more inspiring is that Nature offers a masterclass in optimizing form to suit a purpose.

Think about the sleek, hydrodynamic bodies of marine life that can slice through the water with ease. Another example, the lightweight yet incredibly strong structures found inside bones. These biological designs are beautifully, conceptually elegant in their use of physical geometry and efficiency.

One of the most telling examples of this principle is the Kingfisher’s Beak. Its unique aerodynamic and hydrodynamic shape has actually inspired the design of the nose cone for high-speed trains.

This biomimetic application does two very important things. Firstly, it helps to reduce those pesky sonic booms produced by high-speed trains. Secondly, it significantly increases the overall energy efficiency of the trains by reducing air resistance.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg because there are plenty of other examples of this principle at work. For instance, the study of abalone shells has led to the development of impact-resistant materials. Equally inspiring, the intricate branching patterns of trees have inspired architects to rethink how buildings are distributed loads.

2. Material Science and Composition (The Engineering Challenge)

Nature’s manufacturing paradigm

In this section, we will contrast: comparing inefficient traditional industrial methods (like high heat, harsh chemicals) with nature’s elegant, room-temperature approach of growing materials rather than extracting them.

This level takes us on a journey into the fascinating world of bio-materials. We will now take a close look at their chemistry and fabrication. We explore how life itself creates incredibly robust and functional materials through intricate biological processes.

There’s a crucial distinction here: traditional industrial methods tend to rely on high temperatures, harsh chemicals and resource. These methods are also using intensive extraction processes. And yet, nature manages to achieve all sorts of amazing things at room temperature, using non-toxic, readily available inputs. This represents a whole new paradigm in material science and one that involves growing materials, rather than extracting them.

Case Studies in biological fabrication

In this section, we will introduce two key examples, the Beetle Shell and Mycelium, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of nature’s process.

One particularly striking example of natural manufacturing precision is the Beetle Shell’s Chiral Composite. This is a fantastic illustration of biological fabrication in action, because the shell is made up of a complex, multi-layered composite that is self-assembled through a series of intricate biological processes. And the resulting material is just incredibly strong, yet also light and impact-resistant, a prime example of performance durability in naturally occurring bio-composites.

And then there’s Mycelium, which provides yet another compelling model for material science. This is an intricate, root-like structure of fungi that is able to bind organic waste into all sorts of durable, lightweight, and fully circular bio-composites. It also has the ability to grow into all sorts of shapes and textures – which is just a really cool example of the sort of revolution that’s possible when we start thinking about growing materials, rather than extracting them.

Both Mycelium and the Beetle Shell demonstrate the potential for creating materials that are not only high-performing but also inherently self-assembling and fully circular within natural ecological cycles.

Key properties: consistency and durability

In this final section, we will look at the two core properties that make bio-materials revolutionary.

First, material consistency: We are inspired by the precise self-assembly and hierarchical structuring in biological systems, which lead to exceptional material consistency and predictable performance.

Second, performance durability: We study the durability and resilience of naturally occurring bio-composites. These often exceed many synthetic alternatives, prompting us to uncover the design principles that confer such long-lasting performance.

To illustrate these properties, let’s explore the Beetle Shell’s Chiral Composite, and also check our the details in one of our post. This remarkable structure showcases how a complex, multi-layered composite can be self-assembled to potentially create lightweight, yet incredibly strong and impact-resistant armor. Similarly, Mycelium, the intricate root-like structure of fungi (the subject of our first post), provides another compelling model. Mycelium’s ability to grow into various shapes and textures, binding organic waste into durable, lightweight, and fully circular bio-composites, offers immense potential for sustainable manufacturing. Both examples highlight the potential for creating materials that are not only high-performing but also inherently self-assembling and fully circular within natural ecological cycles.

The Three Levels of Mimétique Design

3. System, Process, and Regeneration (The Strategic Challenge)

This third level, The Strategic Challenge, focuses on System, Process, and Regeneration. The high level focus here is ecosystem design and operational resilience. Specifically, this involves translating fundamental ecological principles into potential industrial infrastructure and dynamic supply chain models.

This approach is anchored in two key concepts. The first is Closed-Loop Metabolism, where the “waste” or output of one system becomes a valuable input for another. The second is Self-Correction, which enables systems to adapt and optimize autonomously. In essence, this strategy moves beyond designing a single product or material. Instead, it ensures that the entire system works together, mimicking the interdependent relationships found in nature. The goal is to build robust systems that function efficiently and withstand disruptions, much like a natural ecosystem sustains itself through change.

Key Concept 1: Closed-Loop Metabolism (Zero-Waste) ♻️

This principle requires that the output (“waste”) of one industrial system is rigorously channeled back to become a valuable input for another part of the production process. This concept is directly inspired by Nature’s zero-waste model, with the ultimate goal being adherence to Zero-Waste Mandates by eliminating discard streams.

We find a core example demonstrating this philosophy in the forest ecosystem’s nutrient cycle. In a forest, every fallen leaf, decaying branch or animal byproduct is meticulously reabsorbed and recycled, which enriches the soil and sustains new life.

We then apply this profound natural paradigm to factory systems. This means designing and implementing operations where every thermal byproduct (heat), water outflow, or material scrap is not discarded. Instead, it is rigorously channeled back into the production process.

Key Concept 2: Self-Correction (Nature’s adaptability) 🔄

If Closed-Loop Metabolism is about eliminating waste, then Self-Correction is about eliminating fragility! This concept is all about building systems that don’t just endure disruption, but they actually get better because of it.

Think about a forest recovering from a wildfire. It doesn’t just return to the way it was. In fact, it adapts, grows new species and uses the disruption to evolve into a more resilient ecosystem. We want to translate that kind of dynamic, autonomous optimization directly into our industrial infrastructure and supply chains.

The idea is to embed the rules of adaptation into the system itself. This means using real-time data to let the factory floor or the supply chain identify its own bottlenecks, reroute materials, and automatically adjust processes without a human having to frantically intervene. The ultimate goal? To design systems that are so inherently smart and robust, they withstand disruptions and constantly seek out the most efficient, resilient operational state. It’s about designing a business that learns and heals on its own!

This holistic integration achieves true Regenerative Manufacturing. Ultimately, this leads to industrial operations that are not only sustainable but actively restorative, mimicking nature’s inherent efficiency and cyclical nature.

Disclaimer: This website reflects conceptual analysis and thought leadership regarding biomimicry principles. It is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute professional engineering, financial, or strategic business advice.

ACCESS WEEKLY MIMÉTIQUE ANALYSIS.

Decode the future of R&D. Receive our curated strategic insights on Zero-Energy Design and Material Innovation.